Land of the Maya

Lubaantun

Lubaantun ("Place of Fallen Stones") is the largest Maya site in Southern Belize. It is well known for the unusual style of construction. All structures are made of limestone blocks with no visible mortar binding them together. The strength of each structure lies in every hand-cut stone, which was carefully measured and shaped to fit snugly next to each neighboring block.

Lubantuun is a late Classic ceremonial center dated to 700-900 AD. Over time, the ground on which Lubantuun was built began to subsist and the mortarless blocks began to tumble. Thereafter, the site was given the name Lubantuun translates to "place of the fallen rocks" from the modern Maya language.

Eleven large structures tower above five main plazas and three ball courts. Unlike most other Maya ceremonial sites, the existing structures are solid and have no doorways. Another unique feature not found in other sites around the region is the rounded corners on the structures. Since no corbeled arches exist at the top of these structures, it is believed that perishable materials such as wood and thatch, were used to build superstructures on top of these pyramids.

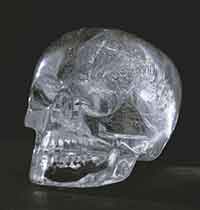

The Mitchell-Hedges Crystal Skull discovered in Mayan ruins called "Lubaantun", City of Fallen Stones, in British Honduras, Now called Belize. The skull was discovered in 1924 by Anna Le Guillon Mitchell-Hedges daughter of F.A. Mitchell-Hedges who was in charge of the digs at Lubaantun. The story goes that his daughter, Anna, was exploring inside some ruins thought to have been a temple, when she found the exquisitely carved crystal skull which was then missing the jawbone. The missing jawbone was found three months later, about 25 feet away from where the top part of the skull was found. There is some evidence that the story of the skull's discovery may be a fabrication.

How Was It Made - And By Whom?

The Mitchell-Hedges skull is made of clear quartz crystal, and both cranium and mandible are believed to have come from the same solid block. It weighs 11.7 pounds and is about five inches high, five inches wide, and seven inches long. Except for slight anomalies in the temples and cheekbones, it is a virtually anatomically correct replica of a human skull. Because of its small size and other characteristics, it is thought more closely to resemble a female skull -- and this has led some to refer to the Mitchell-Hedges skull as a "she."

The Mitchell-Hedges family loaned the skull to Hewlett-Packard Laboratories for extensive study in 1970. Art restorer Frank Dorland oversaw the testing at the Santa Clara, California, computer equipment manufacturer, a leading facility for crystal research. The HP examinations yielded some startling results.

Researchers found that the skull had been carved against the natural axis of the crystal. Modern crystal sculptors always take into account the axis, or orientation of the crystal's molecular symmetry, because if they carve "against the grain," the piece is bound to shatter -- even with the use of lasers and other high-tech cutting methods.

To add to the enigma, HP could find no microscopic scratches on the crystal which would indicate it had been carved with metal instruments. Dorland's best hypothesis for the skull's construction is that it was roughly hewn out with diamonds, and then the detail work was meticulously done with a gentle solution of silicon sand and water. The exhausting job -- assuming it could possibly be done in this way -- would have required man-hours adding up to 300 years to complete.

Under these circumstances, experts believe that successfully crafting a shape as complex as the Mitchell-Hedges skull is impossible; as one HP researcher is said to have remarked, "The damned thing simply shouldn't be."