Pirate Ships

Any ship can be a pirate ship. All you need are pirates!

And the will to do what no one else would think of!

Below are a few of the ships sailed during the Golden Age of Piracy.

If you find any of the information below to be inaccurate, please let us know!

Brigantine

The brigantine was the second most popular type of ship built in the American colonies before 1775. It was a vessel that could be of various sizes, usually in the range of 30 to 150 tons burden, generally a two masted ship, square-rigged on the foremast, and having a fore-and-aft main sail on the main mast and a square main topsail. After 1720 the main square topsail was omitted in most brigantines.

Swifter and more maneuverable than larger ships, the brigantine was often employed for purposes of piracy, espionage, and reconnoitering, or as an attendant upon larger ships for protection.

Caravel (Carvel)

The caravel (also spelled carvel) is a light sailing ship that that was developed by the Portuguese in the late 1400's, and was used for the next 300 years. The Portuguese developed this ship to help them explore the African coast.

The caravel was an improvement on older ships because it could sail very fast and also sail well into the wind (windward). Caravel planking on the hull replaced thinner, less effective planking. Caravels were broad-beamed ships that had 2 or 3 masts with square sails and a triangular sail (called a lanteen) . They were up to about 65 feet long and could carry roughly 130 tons of cargo. Caravels were smaller and lighter than the later Spanish galleons (developed in the 1500's).

Two of Christopher Columbus' three ships were caravels (the Niña and the Pinta).

Carrack

Specific features of the carrack were its rounded stern, with the planks curving around from the sides to the rudder post, the forecastle located directly above the stem, with the bow sprit rising from its top -- an arrangement that had been unaltered since the first "battlements" had been installed on the bow of a sailing warship -- and the aftcastle that formed an integral part of the hull.

The carrack was the definitive beast of burden of the Age of Exploration; Magellan, for example, had an all-carrack fleet with which he set to circumnavigate the globe in 1519. The spacious vessels offered room for a large crew and provisions -- as well as for cargo to be brought back home.

The Dutch Flute

Dutch Flute was a prize in the early 17th Century. Primarily a prize for the shipping world, the Flute was an impressive 300 ton, 80 foot ship that proved inexpensive to build as well as man. The Flute needed only a dozen seamen. With a flat bottom, broad beams, and a round stern, this ship soon became the favored model of a cargo ship. A large part of the popularity of the Flute for commerce was her incredible cargo capacity; about 150% that of similar ships. In this, they soon became a common prey for savvy pirate.

The Frigate

Around 1700, the English began building a class of warship which was only second in size to the Ship-of-the-Line (battleship). Frigates were three-masted with a raised forecastle and quarterdeck. They had anywhere from 24 to 38 guns on her deck. They were faster than the ship-of-the-lines and were used for escort purposes. They were sometimes used to hunt pirates. Only a few pirates were ever in command of a frigate as most pirates exercised discretion and withdrew rather than do battle with a Frigate.

Galleon

Galleons were large ships meant for transporting cargo. Galleons were sluggish behemoths, not able to sail into or near the wind. The Spanish treasure fleets were made of these ships. Although they were sluggish, they weren't the easy target you would expect for they could carry heavy cannon which made a direct assault upon them difficult. She had two to three decks. Most had three masts, forward masts being square-rigged, lateen-sails on the mizzenmast, and a small square sail on her high-rising bow sprit. Some galleons sported 4 masts but these were an exception to the rule.

Junk

The word junk derives from the Portuguese junco, which in turn came from the Javanese word djong, which means ship. The ship has a flat-bottom with no keel, flat bow, and a high stern. A junk's width is about a third of its length and she has a rudder which can be lowered or raised providing excellent steering capabilities. A junk has two or three masts with square sails, made from bamboo, rattan or grass. Contrary to belief, the junk is capable of operating in any seas as she is a very sea-worthy vessel.

Man-O-War

Also called Ships-Of-The-Line, these ships were the "heavy-guns" of the fleet. They resembled galleons in design, but sported heavy fire-power with an average of 65 guns. It was not uncommon to have over 100 guns. They were around 1,000 tons and had 3 masts, which were square-rigged, except for a lateen sail on her aft-mast. Only the three major sea-powers of the time (Spain, England, and France) had an extensive use of these ships.

Meka II

Captain Sinbad built and launched the MEKA II in 1967, and since she has earned the respect of many high seas adventurers for her sail training and historical educational voyages, following in the wake of great pirates and privateers.

The MEKA II has an overall length of 54' and is a half-scale replica of a 17th Century, two masted pirate brigantine armed with 6 cannons. Her home port is Beaufort, North Carolina where locals and tourist take pride in her ongoing efforts to preserve maritime heritage.

For more information on Meka II, visit Pirate-Privateer Productions

Merchant (Pink)

There were two classifications of Pink. The first was a small, flat-bottomed ship with a narrow stern. This ship was derived from the Italian pinco. It was used primarily in the Mediterranean as a cargo ship. In the Atlantic the word pink was used to describe any small ship with a narrow stern, having derived from the Dutch word pincke. They were generally square-rigged and used as merchantmen and warships.

The Naval Sloop

The Naval Sloop was basically a Sloop with more guns and slightly larger. The Naval Sloop was a pirate hunting ship, with a crew of 70 to man this 113 ton, 65 foot fighting ship. The ship is "sharp-ended" to allow for faster attack and is fit with 7 pairs of oars (put through the gun ports) to allow for chase without wind. A well trained crew could fire the 12 nine pound cannons about twice every three minutes.

The Naval Snow

Much like the Naval Square Rigged Brigantine, the Naval Snow was distinguished by her for and aft trysail. This was a preferred ship for the Royal Navy in that, for a 90 ton, 60 foot ship, it could manage well in a light quartering wind. The crew of up to 80 had at its disposal 8 six pound guns that rested behind the canvas strung amidships over the open bulwarks. This was a common patrol ship when the navy finally set to deter pirates from their self determined duty.

The Schooner

Perhaps the best known ship, the Schooner is a little of all of the best features in a pirate ship. Unique to the Schooner is a very narrow hull and shallow draft. The pirates of the North American coast and Caribbean were partial to the Schooner because, for a 100 ton ship loaded with 8 cannons, 75 pirates, and 4 swivel guns, it was still small enough to navigate the shoal waters and to hide in remote coves. The Schooner could also reach 11 knots in a good wind. In short, it was a small, quick, and sturdy work-horse for gentlemen of fortune. the first schooner was being launched at Gloucester, Mass., about 1713.

Shebec (Xebex)

The Shebec was favored among Barbary pirates for she was fast, stable and large. They could reach 200 tons and carried from 4 to 24 cannon. In addition she carried from 60 to 200 crewmen. The Shebec had a pronounced overhanging bow and stern, and three masts which were generally lateen-rigged. In addition to sails she was rowed.

The Sloop

The Sloop was fast, agile, and had a shallow draft. Her size could be as large as 100 tons. She was generally rigged with a large mainsail which was attached to a spar above, to the mast on its foremost edge, and to a long boom below. She could sport additional sails both square and lateen-rigged. She was used mainly in the Caribbean and Atlantic. Today's sailing Yacht is essentially a sloop.

Sq. Rigged Carrier

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries commercial ships were generally called "merchant ships", however mariners reserved such a term for the three masted, square rigged carrier. These ships were large and intended for passengers and cargo. The carrier was a 280 ton ship measuring 80 feet in length. While such a ship could be armed with up to 16 cannons, it is doubtful that a typical crew of about 20 could manage more than three or four such guns. This ship sports finer lines and a little more sail power than the Dutch Flute and could make a trip from England to America in about 4 weeks.

Worms

One of the biggest enemies to these ships, and others, weren't pirates or Naval officers, but worms! The teredo worms (mollusks) infest tropical waters and like to make their homes in the wood of a ship's hull. The worms have shells that remain after the critter has moved on and these shells, like barnacles, build up to rob a ship of her speed and seaworthiness. A ship had to be coated with a mixture of tar, tallow and sulfur two or three times a year to prevent these sorts of pests. Also, a ship with such pests would have to be careened to regain her ever-so-important speed and agility. It was during careening that many a pirate met up with an adversary hoping to catch him in such a state of un-preparedness.

The Pirate Crew

CAPTAIN

Unlike a Naval Captain, who were appointed by their respective governments and who's authority was supreme at all times, most pirate captains were elected by the ships crew and could be replaced at any time by a majority vote of the crewmen. A Captain could be voted out for not being as aggressive in the pursuit of prizes as the crew would have liked. Some were abandoned by their crews for being a little to bloodthirsty and brutal. A few were even murdered by their own men. They were expected to be bold and decisive in battle and also have skill in navigation and seamanship. Above all they had to have the force of personality necessary to hold together such an unruly bunch of seamen. Pirate crews appeared to have followed their Captain's judgment in most matters.

QUARTERMASTER

Pirates delegated unusual amounts of authority to the Quartermaster, who became almost the Captain's equal. The Captain retained unlimited authority during battle, but otherwise he was subject to the Quartermaster in many routine matters. The Quartermaster was elected by the crew to represent their interests and he received an extra share of the booty when it was divided. Above all, he protected the Seaman against each other by maintaining order, settling quarrels, and distributing food and other essentials.

The Quartermaster usually kept the records and account books for the ship. He also took part in all battles and often led the attacks by the boarding parties. If the pirates were successful, he decided what plunder to take. If the pirates decide to keep a captured ship, the Quartermaster often took over as the Captain of that ship.

SAILING MASTER

This was the officer who was in charge of navigation and the sailing of the ship. He directed the course and looked after the maps and instruments necessary for navigation. Since the charts of the era were often inaccurate or nonexistent, his job was a difficult one. It was said a good navigator was worth his weight in gold. He was perhaps the most valued person aboard a ship other than the Captain because so much depended upon his skill.

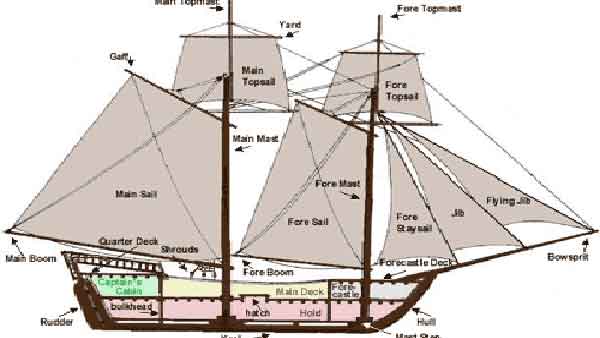

BOATSWAIN

The Boatswain supervised the maintenance of the vessel and its supply stores. He was responsible for inspecting the ship and it's sails and rigging each morning, and reporting their state to the captain. The Boatswain was also in charge of all deck activities, including weighing and dropping anchor, and the handling of the sails.

CARPENTER

The Carpenter was responsible for the maintenance and repair of the wooden hull, masts and yards. He worked under the direction of the ship's Master and Boatswain. The Carpenter checked the hull regularly, placing oakum between the seems of the planks and wooden plugs on leaks to keep the vessel tight. He was highly skilled in his work which he learned through apprenticeship. Often he would have an assistant whom he in turn trained as a carpenter.

MASTER GUNNER

The Master Gunner was responsible for the ship's guns and ammunition. This included sifting the powder to keep it dry and prevent it from separating, insuring the cannon balls were kept free of rust, and all weapons were kept in good repair. A knowledgeable Gunner was essential to the crew's safety and effective use of their weapons.

MATE

On a large ship there was usually more than one Mate aboard. The Mate served as apprentice to the Ship's Master, Boatswain, Carpenter and Gunner. He took care of the fitting out of the vessel, and examined whether it was sufficiently provided with ropes, pulleys, sails, and all the other rigging that was necessary for the voyage. The Mate took care of hoisting the anchor, and during a voyage he checked the tackle once a day. If he observed anything amiss, he would report it to the ship's Master. Arriving at a port, the mate caused the cables and anchors to be repaired, and took care of the management of the sails, yards and mooring of the ship.

SEAMAN

The common sailor, which was the backbone of the ship, needed to know the rigging and the sails. As well as how to steer the ship and applying it to the purposes of navigation. He needed to know how to read the skies, weather, winds and most importantly the moods of his commanders. Other jobs on the ships were surgeon (for large vessels), cooks and cabin boys. There were many jobs divided up amongst the officers, sometimes one man would perform two functions. Mates who served apprenticeships were expected to fill in or take over positions when sickness or death created an opportunity.

PIRATE DEMOCRACY

Unlike traditional Western societies of the time, many pirate crews operated as limited democracies. Pirate communities were some of the first to instate a system of checks and balances similar to the one used by the present-day United States and many other countries. The first record of such a government aboard a pirate sloop dates to the 1600s, a full century before the United States' and France's adoption of democracy in 1789, or Spain's move to democracy in 1812.

Both the captain and the quartermaster were elected by the crew; they, in turn, appointed the other ship's officers. The captain of a pirate ship was often a fierce fighter in whom the men could place their trust, rather than a more traditional authority figure sanctioned by an elite. However, when not in battle, the quartermaster usually had the real authority. Many groups of pirates shared in whatever they seized; pirates injured in battle might be afforded special compensation similar to medical or disability insurance.

There are contemporary records that many pirates placed a portion of any captured money into a central fund that was used to compensate the injuries sustained by the crew. Lists show standardized payments of 600 pieces of eight ($156,000 in modern currency) for the loss of a leg down to 100 pieces ($26,800) for loss of an eye. Often all of these terms were agreed upon and written down by the pirates, but these articles could also be used as incriminating proof that they were outlaws.

Pirates readily accepted outcasts from traditional societies, perhaps easily recognizing kindred spirits, and they were known to welcome them into the pirate fold. For example as many as 40% of the pirate vessels' crews were slaves liberated from captured slavers. Such practices within a pirate crew were tenuous, however, and did little to mitigate the brutality of the pirate's way of life.